In December 1989, I left my office Christmas party early to make my way to Tower Records in London’s Piccadilly.

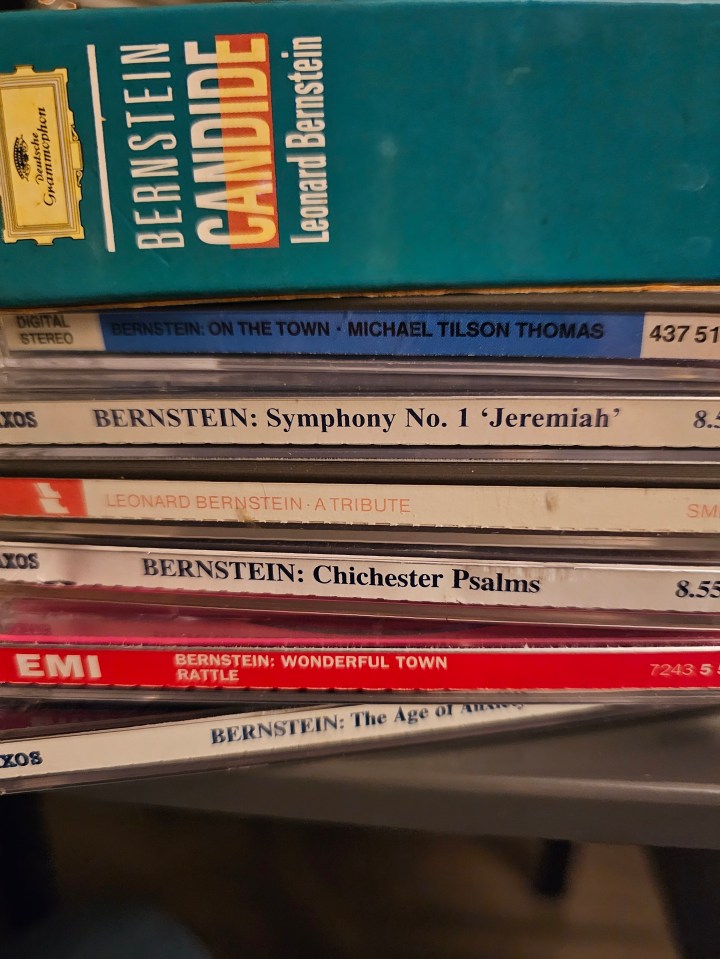

The previous day, we had been at the Barbican to see Leonard Bernstein conducting his operetta Candide. We sat in the front row as one of my musical heroes led a now legendary, and most would agree, definitive performance of his great work.

What I remember of the evening was the sense of anticipation, the feeling that we were about to be in the presence of greatness; how diminutive Bernstein was for someone who, in every other respect, was a giant; how he spoke to the audience at such length and with such passion and insight about Candide, and about the travails of bringing this production to fruition; and the wonder of seeing a great artist exercising complete ownership of his own work. Like the Voltaire novella on which it’s based, Bernstein’s Candide is a work of both big gestures and great subtlety.

The sense of excitement remained with me into the following day, and that’s why I headed to Tower Records where Lenny Bernstein would be doing a record signing. I guess I just wanted to tell him in person how much the previous evening had meant to me. I had no idea whether that was a realistic or worthwhile objective – it was just something I had to do.

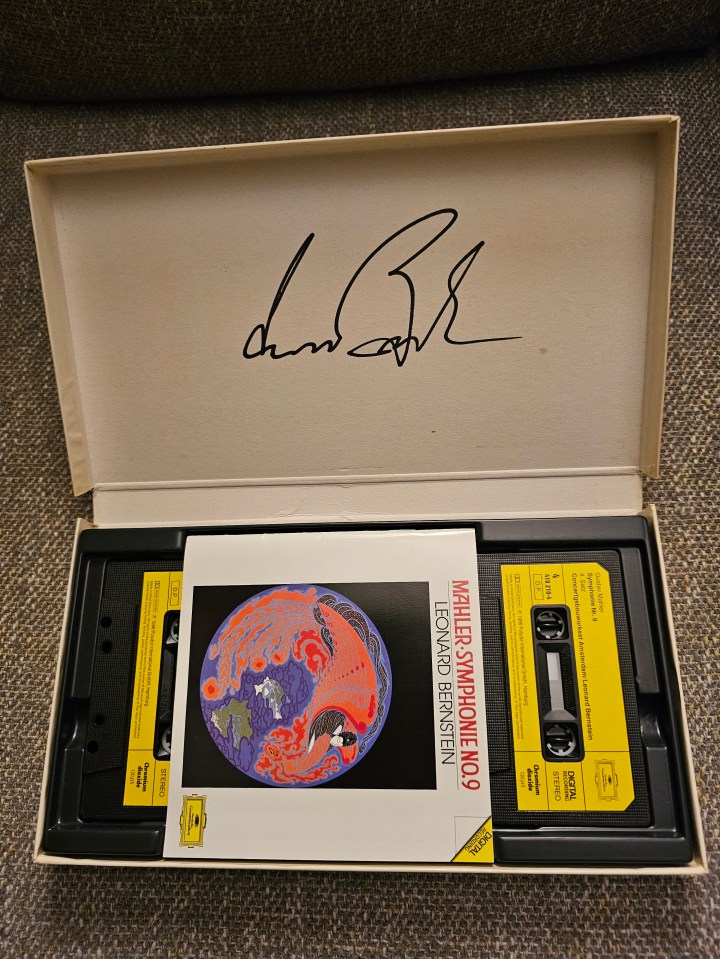

I took along a recording that meant a great deal to me for him to sign: Mahler 9 with the Concertgebouw. I joined the queue, and eventually there he was, sitting at a table with a glass of wine by his side, looking a little jaded. When I found myself in front of him, I said something about how wonderful the Candide had been. He replied, ‘You enjoyed it, did you?’ And there you have it – my conversation with Lenny.

I’ve sometimes reflected on the significance of such encounters. It’s not like you’re suddenly becoming the great person’s friend by turning up at a store and getting them to sign something. But you have at least been in the same space as someone you greatly admire. You have breathed the same air, and an idea has been made flesh.

Maybe it’s stronger than that – maybe it’s a kind of love, in which we extend both our respect and our affection to those we most treasure beyond our immediate family and friends.

What did Lenny mean to me?

If music were just counting and intonation, it would be a pretty empty experience, both for music-maker and audience. It needs heart. It needs passion. It needs something that makes it about the connection between human beings, about what it means to be alive, about filling the darker spaces with light. To be immersed in classical music means you have to give into it. You can’t hold back, and Lenny – forgive the understatement – didn’t.

Music coursed through him, and he externalised that electricity in many of his performances. Excessively so, some might say, his famously controversial, slow-tempo Nimrod being a case in point. But I loved seeing a performer wearing his heart on his sleeve. I worshipped other conductors of that generation – particularly Abbado and Haitink – but Lenny brought something else, not unconnected to his greatness as a composer and an educator.

Which brings me to Maestro, Bradley Cooper’s recently-released Bernstein biopic. There’s a lot of music and music-making in the film, but the focus is Bernstein’s relationship with his wife, Felicia Montealegre, and the strain his sexuality placed on their marriage.

Norman Lebrecht has criticised the film for this, arguing that the focus could have been on, for example, Bernstein’s politics or the creative process. That’s a bit like saying Master and Commander would have been better if it had been more about shipbuilding. For sure, there are different films to be made about Bernstein – and, as documentaries, they have been. But Cooper has chosen to lead with the emotional core of Bernstein’s life, and is right to do so.

We see then how the great artist navigates the space between inspiration and perspiration, where the latter is about desire, the pressures of being in the public eye, social compromises, adulation and self-doubt. We see the fragility of brilliance. We see how mistakes are as much the preserve of gilded lives as of those the rest of us lead. We see how ageing, and the suffocating pressure of legacy, take their toll.

It’s a magnificent achievement – a labour of love, of empathy, of understanding. It’s a serious film. Bradley Cooper, as writer, director and co-lead, must surely now rank at the forefront of cinematic creatives. His co-star, Carey Mulligan, is astonishing in the role of Felicia. Oscars all round.

Maestro should appeal to anyone with an interest in the dynamics of genius, but might resonate a fraction more with those who know something of Bernstein’s life, who the principal characters are, and what the music is. Some of it – West Side Story, of course – we all know. A lot of it would be less familiar to the non-musical film-goer. And I confess I didn’t know Mass until I saw the film.

And then there’s Mahler. Mahler’s music characterised Bernstein’s conducting career more than that of any other composer, to the extent that he was buried with the score for the 5th Symphony laid across his heart. And Maestro turns to the Adagietto from the 5th, written as a love letter to Mahler’s wife Alma, to symbolise Lenny’s feelings for Felicia at the apogee of their relationship (Mahler’s relationship with Alma was, of course, also troubled, albeit in different ways).

Maestro recreates the 1973 performance of the 2nd Symphony, the ‘Resurrection’, in Ely Cathedral. I was too young to have been there, and in any event my father’s Mahler-scepticism (‘too rambling’) kept me at arm’s length from the great Austrian symphonist until I started exploring his music myself through the local library during my student years. My father came to visit, and I sat him down in my little student room and played the 2nd’s choral finale (the Solti/Chicago version, not Lenny’s). He was transfixed, moved and tearful, and asked me to play it again. After that Mahler 2s were a family fixture, particularly at the Proms.

The other scene in the film with the greatest personal resonance for me was the rehearsal of the final chorus from Candide, and not just because we had been at that Barbican performance. Voltaire’s novella ends with Candide telling Dr. Pangloss that, after everything that’s happened in the book’s picaresque tale, ‘…we must go and work in the garden’. This is transformed in Bernstein’s work to:

‘We’re neither pure nor wise nor good; we’ll do the best we know. We’ll build our house, and chop our wood, and make our garden grow.’

A metaphor, of course, for doing our level best to lead a good life, all set to some of the most glorious and uplifting music any human being has yet created. You really don’t need anything more than that as guide rails for living. Thanks, Lenny.

And as Bradley Cooper/Lenny says in the final words of the film, aping Dr Pangloss at the end of Bernstein’s Candide:

‘Any questions?’